Charles Marion Russell Painting Reproductions 2 of 2

1864-1926

American Realist Painter

39 Charles Marion Russell Paintings

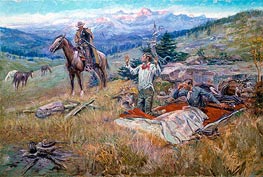

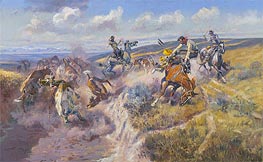

The Call of the Law 1911

Oil Painting

$1407

$1407

Canvas Print

$62.95

$62.95

SKU: RCM-16444

Charles Marion Russell

Original Size: 61 x 91.4 cm

Public Collection

Charles Marion Russell

Original Size: 61 x 91.4 cm

Public Collection

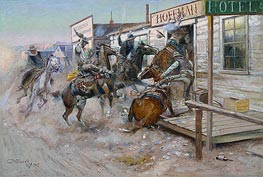

In Without Knocking 1909

Oil Painting

$1436

$1436

Canvas Print

$62.95

$62.95

SKU: RCM-16445

Charles Marion Russell

Original Size: 51 x 76 cm

Amon Carter Museum, Texas, USA

Charles Marion Russell

Original Size: 51 x 76 cm

Amon Carter Museum, Texas, USA

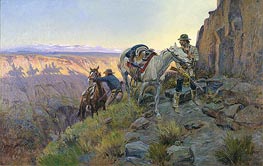

When Shadows Hint Death 1915

Oil Painting

$1378

$1378

SKU: RCM-16446

Charles Marion Russell

Original Size: 76.2 x 101.6 cm

Public Collection

Charles Marion Russell

Original Size: 76.2 x 101.6 cm

Public Collection

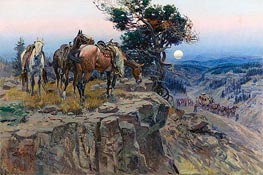

Innocent Allies 1913

Oil Painting

$1474

$1474

Canvas Print

$62.27

$62.27

SKU: RCM-16447

Charles Marion Russell

Original Size: 61 x 91.4 cm

Gilcrease Museum, Tulsa, USA

Charles Marion Russell

Original Size: 61 x 91.4 cm

Gilcrease Museum, Tulsa, USA

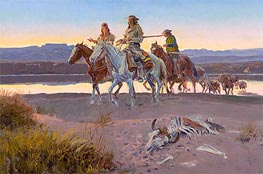

Meat's Not Meat Till It's in the Pan 1915

Oil Painting

$1423

$1423

Canvas Print

$61.75

$61.75

SKU: RCM-16448

Charles Marion Russell

Original Size: 58.4 x 89 cm

Gilcrease Museum, Tulsa, USA

Charles Marion Russell

Original Size: 58.4 x 89 cm

Gilcrease Museum, Tulsa, USA

The Camp Cook's Troubles 1912

Oil Painting

$1904

$1904

Canvas Print

$62.95

$62.95

SKU: RCM-16449

Charles Marion Russell

Original Size: 76.2 x 111.8 cm

Gilcrease Museum, Tulsa, USA

Charles Marion Russell

Original Size: 76.2 x 111.8 cm

Gilcrease Museum, Tulsa, USA

A Tight Dally and a Loose Latigo 1920

Oil Painting

$1505

$1505

Canvas Print

$61.75

$61.75

SKU: RCM-16450

Charles Marion Russell

Original Size: 76.8 x 122.6 cm

Amon Carter Museum, Texas, USA

Charles Marion Russell

Original Size: 76.8 x 122.6 cm

Amon Carter Museum, Texas, USA

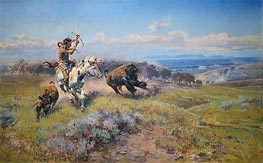

The Buffalo Hunt 1919

Oil Painting

$1417

$1417

Canvas Print

$61.75

$61.75

SKU: RCM-16451

Charles Marion Russell

Original Size: 76.5 x 122.2 cm

Amon Carter Museum, Texas, USA

Charles Marion Russell

Original Size: 76.5 x 122.2 cm

Amon Carter Museum, Texas, USA

When Horses Talk There's Slim Chance for Truce 1915

Oil Painting

$1348

$1348

Canvas Print

$62.27

$62.27

SKU: RCM-16452

Charles Marion Russell

Original Size: 61 x 91.4 cm

Public Collection

Charles Marion Russell

Original Size: 61 x 91.4 cm

Public Collection

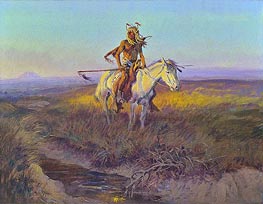

The Scout 1915

Oil Painting

$1010

$1010

Canvas Print

$71.80

$71.80

SKU: RCM-16453

Charles Marion Russell

Original Size: 45.7 x 61 cm

Public Collection

Charles Marion Russell

Original Size: 45.7 x 61 cm

Public Collection

Carson's Men 1913

Oil Painting

$1317

$1317

Canvas Print

$61.77

$61.77

SKU: RCM-16454

Charles Marion Russell

Original Size: 61 x 90.2 cm

Gilcrease Museum, Tulsa, USA

Charles Marion Russell

Original Size: 61 x 90.2 cm

Gilcrease Museum, Tulsa, USA

Single-Handed 1912

Oil Painting

$2027

$2027

Canvas Print

$83.38

$83.38

SKU: RCM-16455

Charles Marion Russell

Original Size: 73.7 x 81.3 cm

Public Collection

Charles Marion Russell

Original Size: 73.7 x 81.3 cm

Public Collection

A Mix Up 1910

Oil Painting

$1782

$1782

Canvas Print

$61.75

$61.75

SKU: RCM-16456

Charles Marion Russell

Original Size: 77.5 x 103 cm

Rockwell Museum of Western Art, New York, USA

Charles Marion Russell

Original Size: 77.5 x 103 cm

Rockwell Museum of Western Art, New York, USA

Fighting Meat 1919

Oil Painting

$1407

$1407

SKU: RCM-16457

Charles Marion Russell

Original Size: unknown

Cincinnati Art Museum, Ohio, USA

Charles Marion Russell

Original Size: unknown

Cincinnati Art Museum, Ohio, USA

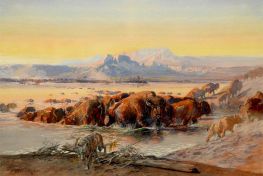

The Upper Missouri in 1840 1902

Paper Art Print

$58.48

$58.48

SKU: RCM-19533

Charles Marion Russell

Original Size: unknown

Amon Carter Museum, Texas, USA

Charles Marion Russell

Original Size: unknown

Amon Carter Museum, Texas, USA