Jacques-Louis David Painting Reproductions 3 of 3

1748-1825

French Neoclassical Painter

62 Jacques-Louis David Paintings

Saint Roch Pleading for the Victims of the Plague 1781

Oil Painting

$4696

$4696

Canvas Print

$114.45

$114.45

SKU: DJL-12876

Jacques-Louis David

Original Size: 259 x 193 cm

Musée des Beaux-Arts, Marseille, France

Jacques-Louis David

Original Size: 259 x 193 cm

Musée des Beaux-Arts, Marseille, France

Hector (Academic Figure of a Man) n.d.

Oil Painting

$1628

$1628

Canvas Print

$66.36

$66.36

SKU: DJL-12877

Jacques-Louis David

Original Size: 123 x 172 cm

Musee Fabre, Montpellier, France

Jacques-Louis David

Original Size: 123 x 172 cm

Musee Fabre, Montpellier, France

The Death of Seneca n.d.

Oil Painting

$5932

$5932

Canvas Print

$74.19

$74.19

SKU: DJL-12878

Jacques-Louis David

Original Size: 122.5 x 155 cm

Petit Palais Musee des Beaux Arts, Paris, France

Jacques-Louis David

Original Size: 122.5 x 155 cm

Petit Palais Musee des Beaux Arts, Paris, France

Portrait of Jacobus Blauw 1795

Oil Painting

$1843

$1843

Canvas Print

$73.17

$73.17

SKU: DJL-12879

Jacques-Louis David

Original Size: 92 x 73 cm

National Gallery, London, UK

Jacques-Louis David

Original Size: 92 x 73 cm

National Gallery, London, UK

Portrait of the Comtesse Vilain XIIII and Her Daughter 1816

Oil Painting

$2543

$2543

Canvas Print

$70.78

$70.78

SKU: DJL-12880

Jacques-Louis David

Original Size: 95 x 76 cm

National Gallery, London, UK

Jacques-Louis David

Original Size: 95 x 76 cm

National Gallery, London, UK

Emperor Napoleon I 1807

Oil Painting

$3266

$3266

Canvas Print

$61.75

$61.75

SKU: DJL-12881

Jacques-Louis David

Original Size: 88.2 x 59.3 cm

Fogg Art Museum at Harvard University, Massachusetts, USA

Jacques-Louis David

Original Size: 88.2 x 59.3 cm

Fogg Art Museum at Harvard University, Massachusetts, USA

Emmanuel Joseph Sieyès 1817

Oil Painting

$1999

$1999

Canvas Print

$71.46

$71.46

SKU: DJL-12882

Jacques-Louis David

Original Size: 97.8 x 74 cm

Fogg Art Museum at Harvard University, Massachusetts, USA

Jacques-Louis David

Original Size: 97.8 x 74 cm

Fogg Art Museum at Harvard University, Massachusetts, USA

Homer and Calliope 1812

Oil Painting

$2496

$2496

Canvas Print

$78.79

$78.79

SKU: DJL-12883

Jacques-Louis David

Original Size: 84.5 x 100.7 cm

Fogg Art Museum at Harvard University, Massachusetts, USA

Jacques-Louis David

Original Size: 84.5 x 100.7 cm

Fogg Art Museum at Harvard University, Massachusetts, USA

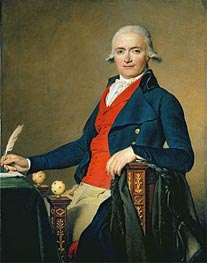

Gaspard Meyer (The Man in the Red Waistcoat) 1795

Oil Painting

$2337

$2337

Canvas Print

$73.68

$73.68

SKU: DJL-12884

Jacques-Louis David

Original Size: 116 x 89.5 cm

Louvre Museum, Paris, France

Jacques-Louis David

Original Size: 116 x 89.5 cm

Louvre Museum, Paris, France

Napoleon Crossing the Alps c.1800

Oil Painting

$3769

$3769

Canvas Print

$79.81

$79.81

SKU: DJL-12885

Jacques-Louis David

Original Size: 271 x 232 cm

Schloss Charlottenburg, Berlin, Germany

Jacques-Louis David

Original Size: 271 x 232 cm

Schloss Charlottenburg, Berlin, Germany

Apollo and Diana Attacking the Children of Niobe n.d.

Oil Painting

$4869

$4869

Canvas Print

$72.32

$72.32

SKU: DJL-12886

Jacques-Louis David

Original Size: 121 x 154 cm

Private Collection

Jacques-Louis David

Original Size: 121 x 154 cm

Private Collection

Antiochus and Stratonice 1774

Oil Painting

$3341

$3341

Canvas Print

$71.46

$71.46

SKU: DJL-12887

Jacques-Louis David

Original Size: 120 x 155 cm

Ecole Nationale Superieure des Beaux-Arts, Paris, France

Jacques-Louis David

Original Size: 120 x 155 cm

Ecole Nationale Superieure des Beaux-Arts, Paris, France

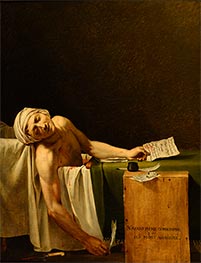

The Death of Marat 1793

Oil Painting

$1924

$1924

Canvas Print

$71.64

$71.64

SKU: DJL-18879

Jacques-Louis David

Original Size: 111.3 x 86 cm

Musee des Beaux Arts, Reims, France

Jacques-Louis David

Original Size: 111.3 x 86 cm

Musee des Beaux Arts, Reims, France

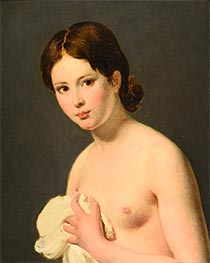

Young Girl c.1795

Oil Painting

$696

$696

Canvas Print

$74.53

$74.53

SKU: DJL-18880

Jacques-Louis David

Original Size: 59.7 x 48 cm

Musee des Beaux Arts, Reims, France

Jacques-Louis David

Original Size: 59.7 x 48 cm

Musee des Beaux Arts, Reims, France