Edgar Degas Painting Reproductions 11 of 13

1834-1917

French Impressionist Painter

312 Edgar Degas Paintings

Dancer in the Wing c.1905

Paper Art Print

$58.48

$58.48

SKU: DEE-11841

Hilaire Germain Edgar Degas

Original Size: unknown

Fitzwilliam Museum, Cambridge, UK

Hilaire Germain Edgar Degas

Original Size: unknown

Fitzwilliam Museum, Cambridge, UK

Self Portrait c.1862

Oil Painting

$838

$838

Canvas Print

$61.75

$61.75

SKU: DEE-11842

Hilaire Germain Edgar Degas

Original Size: 92 x 69 cm

Museu Calouste Gulbenkian, Lisbon, Portugal

Hilaire Germain Edgar Degas

Original Size: 92 x 69 cm

Museu Calouste Gulbenkian, Lisbon, Portugal

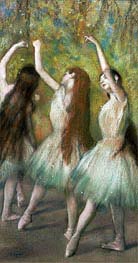

Green Dancers 1878

Paper Art Print

$58.48

$58.48

SKU: DEE-11843

Hilaire Germain Edgar Degas

Original Size: 72.4 x 39.4 cm

Private Collection

Hilaire Germain Edgar Degas

Original Size: 72.4 x 39.4 cm

Private Collection

The ballet scene from Meyerbeer's opera 'Robert ... 1876

Oil Painting

$926

$926

Canvas Print

$86.44

$86.44

SKU: DEE-11844

Hilaire Germain Edgar Degas

Original Size: 76.6 x 81.3 cm

Victoria and Albert Museum, London, UK

Hilaire Germain Edgar Degas

Original Size: 76.6 x 81.3 cm

Victoria and Albert Museum, London, UK

Scene of War in the Middle Ages c.1865

Oil Painting

$1275

$1275

Canvas Print

$88.96

$88.96

SKU: DEE-11845

Hilaire Germain Edgar Degas

Original Size: 85 x 147 cm

Musee d'Orsay, Paris, France

Hilaire Germain Edgar Degas

Original Size: 85 x 147 cm

Musee d'Orsay, Paris, France

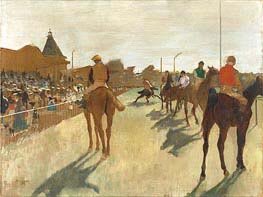

The Parade (Race Horses in Front of the Stands) c.1866/68

Oil Painting

$797

$797

Canvas Print

$61.75

$61.75

SKU: DEE-11846

Hilaire Germain Edgar Degas

Original Size: 46 x 61 cm

Musee d'Orsay, Paris, France

Hilaire Germain Edgar Degas

Original Size: 46 x 61 cm

Musee d'Orsay, Paris, France

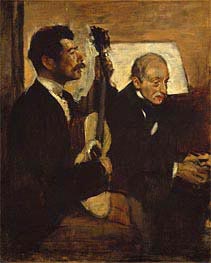

Degas's Father Listening to Lorenzo Pagans ... c.1869/72

Oil Painting

$788

$788

SKU: DEE-11850

Hilaire Germain Edgar Degas

Original Size: 81.6 x 65.1 cm

Boston Museum of Fine Arts, Massachusetts, USA

Hilaire Germain Edgar Degas

Original Size: 81.6 x 65.1 cm

Boston Museum of Fine Arts, Massachusetts, USA

Scene from the Steeplechase: The Fallen Jockey 1866

Oil Painting

$898

$898

Canvas Print

$78.27

$78.27

SKU: DEE-11851

Hilaire Germain Edgar Degas

Original Size: 180 x 152 cm

National Gallery of Art, Washington, USA

Hilaire Germain Edgar Degas

Original Size: 180 x 152 cm

National Gallery of Art, Washington, USA

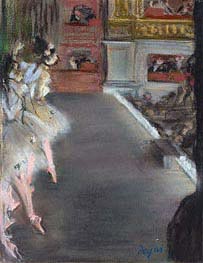

Dancers at the Old Opera House c.1877

Paper Art Print

$58.48

$58.48

SKU: DEE-11852

Hilaire Germain Edgar Degas

Original Size: 21.8 x 17.1 cm

National Gallery of Art, Washington, USA

Hilaire Germain Edgar Degas

Original Size: 21.8 x 17.1 cm

National Gallery of Art, Washington, USA

Woman Ironing c. 1876/87

Oil Painting

$758

$758

Canvas Print

$74.87

$74.87

SKU: DEE-11853

Hilaire Germain Edgar Degas

Original Size: 81.3 x 66 cm

National Gallery of Art, Washington, USA

Hilaire Germain Edgar Degas

Original Size: 81.3 x 66 cm

National Gallery of Art, Washington, USA

Girl Drying Herself 1885

Paper Art Print

$58.48

$58.48

SKU: DEE-11854

Hilaire Germain Edgar Degas

Original Size: 80.1 x 51.2 cm

National Gallery of Art, Washington, USA

Hilaire Germain Edgar Degas

Original Size: 80.1 x 51.2 cm

National Gallery of Art, Washington, USA

Dancers Backstage c.1876/83

Oil Painting

$477

$477

Canvas Print

$61.75

$61.75

SKU: DEE-11855

Hilaire Germain Edgar Degas

Original Size: 24.2 x 18.8 cm

National Gallery of Art, Washington, USA

Hilaire Germain Edgar Degas

Original Size: 24.2 x 18.8 cm

National Gallery of Art, Washington, USA

Actress in Her Dressing Room c.1879

Oil Painting

$836

$836

Canvas Print

$71.01

$71.01

SKU: DEE-11856

Hilaire Germain Edgar Degas

Original Size: 85.4 x 75.6 cm

Norton Simon Museum of Art, Pasadena, USA

Hilaire Germain Edgar Degas

Original Size: 85.4 x 75.6 cm

Norton Simon Museum of Art, Pasadena, USA

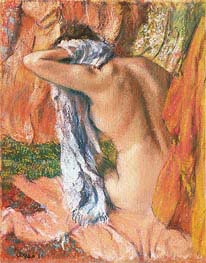

After the Bath c.1890/93

Paper Art Print

$59.77

$59.77

SKU: DEE-11857

Hilaire Germain Edgar Degas

Original Size: 66 x 52.7 cm

Norton Simon Museum of Art, Pasadena, USA

Hilaire Germain Edgar Degas

Original Size: 66 x 52.7 cm

Norton Simon Museum of Art, Pasadena, USA

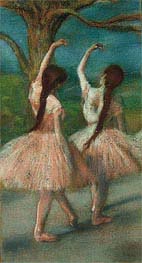

Dancers in Pink c.1883

Paper Art Print

$58.48

$58.48

SKU: DEE-11858

Hilaire Germain Edgar Degas

Original Size: 73 x 40 cm

Norton Simon Museum of Art, Pasadena, USA

Hilaire Germain Edgar Degas

Original Size: 73 x 40 cm

Norton Simon Museum of Art, Pasadena, USA

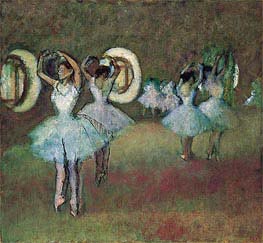

Dancers in the Rotunda at the Paris Opera 1895

Oil Painting

$921

$921

Canvas Print

$61.75

$61.75

SKU: DEE-11859

Hilaire Germain Edgar Degas

Original Size: 88.6 x 95.9 cm

Norton Simon Museum of Art, Pasadena, USA

Hilaire Germain Edgar Degas

Original Size: 88.6 x 95.9 cm

Norton Simon Museum of Art, Pasadena, USA

Dancers in the Wings 1880

Paper Art Print

$58.48

$58.48

SKU: DEE-11860

Hilaire Germain Edgar Degas

Original Size: 69.2 x 50.2 cm

Norton Simon Museum of Art, Pasadena, USA

Hilaire Germain Edgar Degas

Original Size: 69.2 x 50.2 cm

Norton Simon Museum of Art, Pasadena, USA

Portrait of Madame Dietz-Monnin 1879

Paper Art Print

$58.48

$58.48

SKU: DEE-11861

Hilaire Germain Edgar Degas

Original Size: 47 x 31.8 cm

Norton Simon Museum of Art, Pasadena, USA

Hilaire Germain Edgar Degas

Original Size: 47 x 31.8 cm

Norton Simon Museum of Art, Pasadena, USA

The Star: Dancer on Point c.1878

Paper Art Print

$58.48

$58.48

SKU: DEE-11862

Hilaire Germain Edgar Degas

Original Size: 56.5 x 75.6 cm

Norton Simon Museum of Art, Pasadena, USA

Hilaire Germain Edgar Degas

Original Size: 56.5 x 75.6 cm

Norton Simon Museum of Art, Pasadena, USA

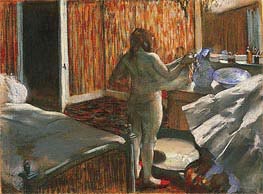

Woman Combing Her Hair Before a Mirror c.1877

Oil Painting

$625

$625

Canvas Print

$61.75

$61.75

SKU: DEE-11863

Hilaire Germain Edgar Degas

Original Size: 46.7 x 32.4 cm

Norton Simon Museum of Art, Pasadena, USA

Hilaire Germain Edgar Degas

Original Size: 46.7 x 32.4 cm

Norton Simon Museum of Art, Pasadena, USA

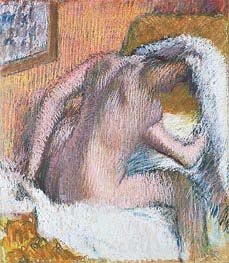

Woman Drying Her Hair c.1905

Paper Art Print

$66.19

$66.19

SKU: DEE-11864

Hilaire Germain Edgar Degas

Original Size: 71.4 x 62.9 cm

Norton Simon Museum of Art, Pasadena, USA

Hilaire Germain Edgar Degas

Original Size: 71.4 x 62.9 cm

Norton Simon Museum of Art, Pasadena, USA

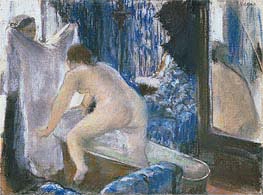

Woman Drying Herself After the Bath c.1876/77

Paper Art Print

$80.73

$80.73

SKU: DEE-11865

Hilaire Germain Edgar Degas

Original Size: 45.7 x 60.3 cm

Norton Simon Museum of Art, Pasadena, USA

Hilaire Germain Edgar Degas

Original Size: 45.7 x 60.3 cm

Norton Simon Museum of Art, Pasadena, USA

Woman Getting Out of the Bath c.1877

Paper Art Print

$58.48

$58.48

SKU: DEE-11866

Hilaire Germain Edgar Degas

Original Size: 15.9 x 21.6 cm

Norton Simon Museum of Art, Pasadena, USA

Hilaire Germain Edgar Degas

Original Size: 15.9 x 21.6 cm

Norton Simon Museum of Art, Pasadena, USA

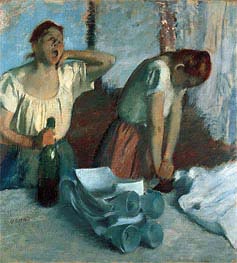

Women Ironing c.1884

Oil Painting

$809

$809

Canvas Print

$72.58

$72.58

SKU: DEE-11867

Hilaire Germain Edgar Degas

Original Size: 82.2 x 75.6 cm

Norton Simon Museum of Art, Pasadena, USA

Hilaire Germain Edgar Degas

Original Size: 82.2 x 75.6 cm

Norton Simon Museum of Art, Pasadena, USA