Caspar David Friedrich Painting Reproductions 5 of 5

1774-1840

German Romanticism Painter

105 Caspar David Friedrich Paintings

Two Men by the Sea 1817

Oil Painting

$940

$940

Canvas Print

$70.78

$70.78

SKU: FCD-18810

Caspar David Friedrich

Original Size: 51 x 66 cm

Gemaldegalerie, Berlin, Germany

Caspar David Friedrich

Original Size: 51 x 66 cm

Gemaldegalerie, Berlin, Germany

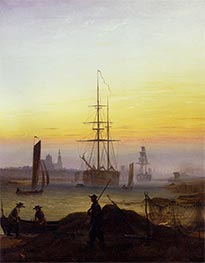

The Port of Greifswald c.1818/20

Oil Painting

$1343

$1343

Canvas Print

$72.83

$72.83

SKU: FCD-18811

Caspar David Friedrich

Original Size: 90 x 70 cm

Gemaldegalerie, Berlin, Germany

Caspar David Friedrich

Original Size: 90 x 70 cm

Gemaldegalerie, Berlin, Germany

The Giant Mountains c.1830/35

Oil Painting

$1247

$1247

Canvas Print

$66.36

$66.36

SKU: FCD-18812

Caspar David Friedrich

Original Size: 72 x 102 cm

Gemaldegalerie, Berlin, Germany

Caspar David Friedrich

Original Size: 72 x 102 cm

Gemaldegalerie, Berlin, Germany

Sea Coast in the Moonlight c.1830

Oil Painting

$1350

$1350

Canvas Print

$73.68

$73.68

SKU: FCD-18813

Caspar David Friedrich

Original Size: 77 x 97 cm

Gemaldegalerie, Berlin, Germany

Caspar David Friedrich

Original Size: 77 x 97 cm

Gemaldegalerie, Berlin, Germany

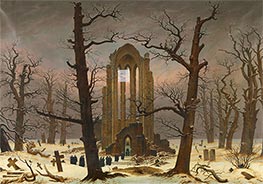

Monastery Cemetery in the Snow c.1819

Oil Painting

$2386

$2386

Canvas Print

$65.51

$65.51

SKU: FCD-18814

Caspar David Friedrich

Original Size: 120 x 173 cm

Gemaldegalerie, Berlin, Germany

Caspar David Friedrich

Original Size: 120 x 173 cm

Gemaldegalerie, Berlin, Germany

Sailing Ship c.1815

Oil Painting

$1235

$1235

Canvas Print

$64.83

$64.83

SKU: FCD-19387

Caspar David Friedrich

Original Size: 96 x 74.5 cm

Public Collection

Caspar David Friedrich

Original Size: 96 x 74.5 cm

Public Collection

Cross on the Baltic Sea 1815

Oil Painting

$734

$734

Canvas Print

$61.75

$61.75

SKU: FCD-19388

Caspar David Friedrich

Original Size: 44.7 x 32 cm

Public Collection

Caspar David Friedrich

Original Size: 44.7 x 32 cm

Public Collection

Ruins of Eldena Abbey in the Giant Mountains c.1830/34

Oil Painting

$2007

$2007

Canvas Print

$66.36

$66.36

SKU: FCD-19773

Caspar David Friedrich

Original Size: 72 x 101 cm

Pomeranian State Museum, Greifswald, Germany

Caspar David Friedrich

Original Size: 72 x 101 cm

Pomeranian State Museum, Greifswald, Germany

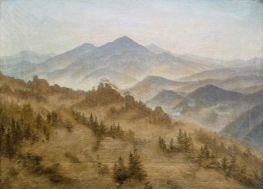

Landscape with the Rosenberg in the Bohemian Mountains 1835

Oil Painting

$1073

$1073

Canvas Print

$61.75

$61.75

SKU: FCD-19774

Caspar David Friedrich

Original Size: 35 x 48.5 cm

Stadel Museum, Frankfurt, Germany

Caspar David Friedrich

Original Size: 35 x 48.5 cm

Stadel Museum, Frankfurt, Germany