Pierre-Auguste Renoir Painting Reproductions 21 of 21

1841-1919

French Impressionist Painter

Pierre-Auguste Renoir created some of the most charming paintings of Impressionist art. Trained as a porcelain painter in a small Paris factory, he made the transition from artisan to artist at the age of 19. Throughout his long career, and despite many changes of style, his paintings always remained joyful. They evoke a dreamy, carefree world full of light and color where beautiful women dance with their lovers.

After struggling for more than 15 years - his Impressionist canvases were derided by the critics -Renoir made his name as a society portrait painter when he was nearly 40. Around this time he married and settled into a happy family life. Later he became crippled by rheumatism and moved south to the Riviera, where he spent his final years painting every day until his death at the age of 78.

Pierre-Auguste Renoir was born at Limoges in mid-France on 25 February 1841, the fourth of his parents' five children. His father Leonard was a tailor; his mother, Marguerite, a seamstress. The family moved to Paris when Renoir was aged four so he grew up in the capital - at first in a run-down apartment in the courtyard of the Louvre, which was then still a royal palace.

The Renoir household was crowded and hardworking, but the boy had a happy childhood distinguished by the discovery that he had a beautiful voice. The composer Gounod proposed to arrange a complete musical education for him, with a place in the chorus of the Paris Opera. But even at 13, Renoir somehow felt that he was no' 'made for that sort of thing'. Instead, he took u another offer - he became an apprentice decorative painter in a small porcelain factory.

Auguste proved so skillful at the job that he was nick-named Mr Rubens and was soon given the task of painting profiles of Marie-Antoinette on the fine white cups. He earned a good living at his craft for five years, before the job of hand-painting was made obsolete by the invention of a mechanical stamping process. It was his first real contact with 'the machine', and turned him against mass-production and standardization for life.

Visits to the Louvre

During his time at the factory, Renoir would visit the art galleries of the Louvre during his lunch hours. His great loves were the exquisite 18th century pictures of courtly gaiety painted by Watteau, Boucher and Fragonard, and the dramatic, colorful canvases of Delacroix. But as he told his son Jean, he was most inspired by a superb 16th-century sculpture, the Fountain of the Innocents. And after a year spent painting blinds and a series of murals for cafes, he decided to become an artist.

In 1862, at the age of 21, Renoir became a student at the studio of Charles Gleyre, a very well-known private art school in Paris. Though academic and traditional in character, it gave him an excellent training with plenty of time to go to the Louvre and study the Old Masters. But Gleyre also stressed the importance of sketching out-of-doors, and encouraged him to visit the Forest of Fontainebleau. This feature of Gleyre's teaching and his remarkable group of young art students had a profound effect on Renoir's career.

Among the students were Claude Monet, Alfred Sisley and Frederic Bazille, through whom. Renoir met Edgar Degas and Edouard Manet, as well as many leading writers and critics. Together they gradually forged a close-knit group that met regularly in the Paris cafes to discuss their theories, and the ideas of Impressionism emerged.

Working closely with Monet in the Forest of Fontainebleau (a two-day walk from Paris), Renoir gradually developed his own style. But their collaboration reached a climax in the summer of 1869 when, working together at the popular river-side restaurant known as La Grenouillere, the two men produced the canvases which are now regarded as the first Impressionist paintings.

These were days of financial hardship for both men. Renoir at least had some help from his family, and took bread and scraps for Monet from his table. But neither had cash to spare for paint or canvas. It was only money from Bazille, who had a small private income, which kept them going.

Renoir in the cavalry

In 1870, this period of intense creativity was brought to an abrupt halt by the Franco-Prussian War. Renoir was called up, and found himself training horses for the cavalry in the Pyrenees, far from the fighting. He returned to Paris in the middle of the bitter Commune battle of 1871, but was lucky enough to have influential friends on both sides who made it possible for him to travel in and out of the city. Renoir continued to paint and the group slowly reformed, though without Bazille, who had been killed in the war. Through Monet, Renoir now met Paul Durand-Ruel, the first art-dealer to support the Impressionists, who agreed to take his work. Soon he was selling enough to move into a large studio in the Rue St Georges. After a sequence of garret studios over the years, he now laughingly declared he had 'arrived'.

This studio, which he occupied for over ten years, became an important meeting place for the Impressionist group and its associates. Renoir's younger brother Edmond, who had emerged as a leading writer and art critic, lived downstairs and made the studio almost too much of a meeting place. Renoir was forced at times to seek small studios for the peace he needed to work. Skinny, bearded and immensely charming, with a nervous, modest manner, Renoir inspired extraordinary affection among his friends. Although not demonstrative - he hated any public show of emotion - he showed intense loyalty and love with acts of quiet generosity. One of his lifelong friends, the artist Paul Cezanne, was the complete opposite. Where Cezanne was suspicious of people, Renoir would not waste his energy worrying about being exploited. 'People love to be nice,' he said, 'but you must give them the chance.'

Even with the new studio, Renoir's money problems were far from over. During the 1870s Renoir's work, like that of other Impressionist painters, was ignored or ridiculed by the academic critics - one of his nudes was once compared to a 'mass of rotting flesh'. But gradually, a small and devoted band of enthusiasts developed.

One of them, Victor Chocquet, became a particular admirer and proceeded to form a considerable collection of Renoir's work. This gave the painter enormous confidence at a difficult time, but on its own it was not enough to support him. He was still dependent on portrait commissions gained via the Salon, until enlightened middle-class families like the Charpentiers and the Berards became his patrons, enabling him to continue with the more experimental Parisian scenes.

Through all these years Renoir had remained a bachelor. There had been romances, probably including one with Lise Trehot whom he painted so often in the 1860s, but Renoir seems always to have regarded the idea of marriage and children as a distraction from the focus of his life - painting.

But around the age of 40, he met Aline Charigot, a pretty girl some 20 years younger than himself, who had occasionally modeled for him. Their relationship developed during the summer of 1881, while he was working on the great masterpiece of his Impressionist period, The Luncheon of the Boating Party, for which she was one of the models. He taught her to swim, and they danced and went boating together. The gentle Aline had almond eyes and 'she walked on the grass without hurting it', but though they loved each other, their affair was not to be straightforward.

Renoir was at a crisis in his painting. Despite Aline's suggestion that they should go and stay in her small home village in Burgundy, he was reluctant to leave Paris and equally reluctant to have children. Aline called things off. Renoir started to travel intensively: first to Normandy, then Algeria, a country he associated with Delacroix, then to Spain and Italy to see the works of the Old Masters - Velazquez in Madrid, Titian in Venice, and Raphael in Rome - and the murals at Pompeii.

A wife and children

But Renoir did not forget Aline, and returned to Paris to be with her. It was to be a relationship of harmony and happiness. She brought him peace of mind as well as children to paint and, as he put it, 'Time to think. She kept an atmosphere of activity around me exactly suited to my needs and concerns.'

Back in his old Rue St Georges studio, Renoir absorbed the visual impressions of his travels into a new way of painting. The so-called 'harsh' style he developed first created further difficulties for his dealer, and it was only the huge enthusiasm of Americans for his work from 1885 that enabled Renoir to support Aline and their newly-born son in reasonable comfort. In 1890 the couple married. Though not yet rich, he was able to move with his family to a larger house in Montmartre and to take on help for Aline. Gabrielle Renard, a distant cousin of Aline's, arrived in 1894. Aged just 15, she had never before left the village of Essones in Burgundy where she and Aline were born. The rosy-skinned, dark-haired young girl soon became part of the family, helping to bring up the younger sons Jean and Claude, and frequently posed as a model.

Renoir enjoyed family life, working hard - and by now selling well - seeing friends every Saturday night, when Aline would hold 'open-house', and visiting his mother on Sundays. But disaster was soon to strike in the form of a serious illness. In 1897, he broke his arm falling off a bicycle, and this brought on the first attack of the muscular rheumatism that slowly started to cripple him and never left him free from pain for the rest of his life. By enormous force of will, aided by the devotions of Aline, Gabrielle and their friends, he somehow continued to paint.

To relieve the pain, Renoir spent increasingly long periods in the warmth of the South of France. In 1907, he built a beautiful house in Cagnes on the Riviera. With its many olive trees and orange blossom, and its views over the Mediterranean, 'Les Collettes' became his base for painting. The brilliant light and relaxed atmosphere helped ease his muscular pain and released a flood of creativity in a colorful, classical style.

However, the beauty of the place could not cure rheumatism. By 1908 Renoir could only walk with sticks. By 1912, his arms and legs were crippled and he was confined to a wheelchair. Nonetheless he continued to paint virtually non-stop, only halting briefly at Aline's death in 1915.

In his last years, Renoir took up sculpture - with two young sculptors acting as his hands, since his own were too crippled to use. The fact that these sculptures are unmistakably Renoir's bears witness to his exceptional ability to communicate.

Renoir painted to the end, working in a special glass studio in his garden. He was carried there daily in his sedan chair, always wearing his white out-of-doors hat, and placed in his wheelchair. Gabrielle would push the paintbrush between his twisted fingers. One day, after Renoir had painted some anemones a maid had brought him, he asked a friend to take his brush, saying T think I am beginning to understand something about it.' He died later that night, on 3 December 1919.

Painting for Pleasure

For Renoir, painting was a way of expressing his pleasure in life. He always enjoyed portraying his friends and lovers, and was never ashamed of making pretty pictures.

'Why shouldn't art be pretty?' Renoir asked once. 'There are enough unpleasant things in the world.' This simple statement sums up his attitude to both life and painting - he had a tremendous capacity for enjoyment, and his art was an expression of his pleasure in life. Renoir only worked when he felt happy, and he deliberately chose subjects that he considered attractive: lush landscapes, fruit and flowers, people enjoying themselves, children playing and, above all, beautiful women.

Nothing gave him greater pleasure than painting women, and although our idea of fashionable beauty may have changed considerably since Renoir's time, the young women we see in his paintings still evoke an era when living in Paris was fun. He was brought up the son of a tailor in the center of the city, and his models are invariably working girls - seamstresses, milliners, actresses -who, he once said, had the precious gift of living for the moment.

Natural as it seems now, Renoir's choice of subject matter was radical and daring when he decided at the age of 21 to enroll as an art student at the studio of Charles Gleyre. The Paris art world was still dominated by the official Salon, which preferred to exhibit works on historical and literary themes, painted in a realistic style. Only in the past few years had younger artists, notably Gustave Courbet, turned to everyday subjects which were more expressive of a fast-changing France. Renoir quickly found that he was more interested in life on the street corner than in the usual studio practice of copying plaster casts of antique sculpture. His teacher could not persuade him that the big toe of a Roman consul should be any more majestic than the toe of a local coal man. One day, exasperated with his pupil, Gleyre said, 'No doubt you took up painting just to amuse yourself. And Renoir replied, 'Certainly. If it didn't amuse me I wouldn't be doing it.'

The impressionist years

While studying at Gleyre's studio, Renoir became friendly with a group of fellow students, dominated by the dynamic personality of Claude Monet, who were later to become famous as the Impressionists. Together they went on painting trips to the Forest of Fontainebleau, 40 miles south of Paris, where they worked out in the open air. Renoir, very impressed by Courbet, used subdued browns and blacks in his work. But one day the artist Narcisse Diaz chanced upon him in the forest and, examining Renoir's canvas, asked 'Why the devil do you paint in such dark colors?'

This encouraged Renoir to use the lighter, rainbow colors he instinctively preferred and which he had learned to handle during his early years as a porcelain painter.

During the late 1860s, Monet and Renoir worked very closely together, for they were both attracted by sparkling river scenes and views of bustling Paris. Several of their pictures at this time are of almost identical scenes, but Renoir's style is softer and more delicate than Monet's. Working out of doors, where the light could not be controlled as in a studio, they had to paint quickly to capture the colors in nature before they changed - for example, when clouds covered the sun. So they made no attempt to blend their brushstrokes in the traditional way. Instead they placed different colors side by side, in the manner soon to be generally described as Impressionist.

Renoir enjoyed painting landscapes, but he was always more interested in people. Throughout his life he included his friends and lovers in his pictures - initially, as a penniless artist, they were the only models available to him. Some of their faces are distinctively 'Renoir, with almond-shaped eyes and luxuriant hair, but what he looked for especially in a model was 'an air of serenity and a good skin that 'took the light'. Some of Renoir's most successful early works are portraits, and his graceful, gentle style was particularly suited to painting children.

During his Impressionist years, Renoir developed a fascination with the effect of light passing through foliage to fall as dappled shadows on the ground, and on human forms. In his painting Le Moulin de la Galette, a large, complex composition, Renoir used the light passing through the trees to unite his figures with their surroundings. Although Renoir painted this work in his studio, he visited its location - a Montmartre dance-hall - every day, immersing himself in the life of the area and making sketches on the spot. Throughout the 1870s Renoir exhibited regularly with the Impressionists, but he also submitted paintings to the Salon. He was always more traditional than the other Impressionists and never for a moment considered himself a revolutionary. While his anarchist friend, the painter Camille Pissarro, wanted to burn down the Louvre, Renoir was a frequent visitor to the gallery.

A change of style

At first he saw no contradiction between his Impressionist insistence on painting directly from nature and his reverent study of Old Masters. But in 1883, following a trip to Italy, Renoir was no longer able to reconcile the two. He told a friend: T had traveled as far as Impressionism could take me and I realized that I could neither paint nor draw.' Subsequently, Renoir dramatically changed his style, and developed a 'harsh' technique, surrounding his figures with hard, sinuous outlines. In The Bathers (1884) he adopted the Old Masters' method of making detailed preparatory drawings. The resulting work is as flat and decorative as a mural at Pompeii.

By the 1890s, these harsh outlines had melted again as Renoir returned to a style more in harmony with his instincts. He began to use warmer colors, especially reds - possibly as a result of two earlier trips to Algeria where he had been most impressed by the hot, sultry light. He painted his children, their beautiful, robust nurse Gabrielle, and a variety of large, sensual nudes, all glowing with radiant color.

Renoir also did a number of flower paintings, in which he experimented with the same rosy flesh tints he used for his nudes. And at the end of his life, when his hands were increasingly crippled by rheumatism, Renoir began to execute small bronze sculptures with the help of studio assistants. These solid, rounded figures were yet another expression of his endless delight in the human form. T never think,' he said, 'that I have finished a nude, until I feel that I could pinch it.'

After struggling for more than 15 years - his Impressionist canvases were derided by the critics -Renoir made his name as a society portrait painter when he was nearly 40. Around this time he married and settled into a happy family life. Later he became crippled by rheumatism and moved south to the Riviera, where he spent his final years painting every day until his death at the age of 78.

Pierre-Auguste Renoir was born at Limoges in mid-France on 25 February 1841, the fourth of his parents' five children. His father Leonard was a tailor; his mother, Marguerite, a seamstress. The family moved to Paris when Renoir was aged four so he grew up in the capital - at first in a run-down apartment in the courtyard of the Louvre, which was then still a royal palace.

The Renoir household was crowded and hardworking, but the boy had a happy childhood distinguished by the discovery that he had a beautiful voice. The composer Gounod proposed to arrange a complete musical education for him, with a place in the chorus of the Paris Opera. But even at 13, Renoir somehow felt that he was no' 'made for that sort of thing'. Instead, he took u another offer - he became an apprentice decorative painter in a small porcelain factory.

Auguste proved so skillful at the job that he was nick-named Mr Rubens and was soon given the task of painting profiles of Marie-Antoinette on the fine white cups. He earned a good living at his craft for five years, before the job of hand-painting was made obsolete by the invention of a mechanical stamping process. It was his first real contact with 'the machine', and turned him against mass-production and standardization for life.

Visits to the Louvre

During his time at the factory, Renoir would visit the art galleries of the Louvre during his lunch hours. His great loves were the exquisite 18th century pictures of courtly gaiety painted by Watteau, Boucher and Fragonard, and the dramatic, colorful canvases of Delacroix. But as he told his son Jean, he was most inspired by a superb 16th-century sculpture, the Fountain of the Innocents. And after a year spent painting blinds and a series of murals for cafes, he decided to become an artist.

In 1862, at the age of 21, Renoir became a student at the studio of Charles Gleyre, a very well-known private art school in Paris. Though academic and traditional in character, it gave him an excellent training with plenty of time to go to the Louvre and study the Old Masters. But Gleyre also stressed the importance of sketching out-of-doors, and encouraged him to visit the Forest of Fontainebleau. This feature of Gleyre's teaching and his remarkable group of young art students had a profound effect on Renoir's career.

Among the students were Claude Monet, Alfred Sisley and Frederic Bazille, through whom. Renoir met Edgar Degas and Edouard Manet, as well as many leading writers and critics. Together they gradually forged a close-knit group that met regularly in the Paris cafes to discuss their theories, and the ideas of Impressionism emerged.

Working closely with Monet in the Forest of Fontainebleau (a two-day walk from Paris), Renoir gradually developed his own style. But their collaboration reached a climax in the summer of 1869 when, working together at the popular river-side restaurant known as La Grenouillere, the two men produced the canvases which are now regarded as the first Impressionist paintings.

These were days of financial hardship for both men. Renoir at least had some help from his family, and took bread and scraps for Monet from his table. But neither had cash to spare for paint or canvas. It was only money from Bazille, who had a small private income, which kept them going.

Renoir in the cavalry

In 1870, this period of intense creativity was brought to an abrupt halt by the Franco-Prussian War. Renoir was called up, and found himself training horses for the cavalry in the Pyrenees, far from the fighting. He returned to Paris in the middle of the bitter Commune battle of 1871, but was lucky enough to have influential friends on both sides who made it possible for him to travel in and out of the city. Renoir continued to paint and the group slowly reformed, though without Bazille, who had been killed in the war. Through Monet, Renoir now met Paul Durand-Ruel, the first art-dealer to support the Impressionists, who agreed to take his work. Soon he was selling enough to move into a large studio in the Rue St Georges. After a sequence of garret studios over the years, he now laughingly declared he had 'arrived'.

This studio, which he occupied for over ten years, became an important meeting place for the Impressionist group and its associates. Renoir's younger brother Edmond, who had emerged as a leading writer and art critic, lived downstairs and made the studio almost too much of a meeting place. Renoir was forced at times to seek small studios for the peace he needed to work. Skinny, bearded and immensely charming, with a nervous, modest manner, Renoir inspired extraordinary affection among his friends. Although not demonstrative - he hated any public show of emotion - he showed intense loyalty and love with acts of quiet generosity. One of his lifelong friends, the artist Paul Cezanne, was the complete opposite. Where Cezanne was suspicious of people, Renoir would not waste his energy worrying about being exploited. 'People love to be nice,' he said, 'but you must give them the chance.'

Even with the new studio, Renoir's money problems were far from over. During the 1870s Renoir's work, like that of other Impressionist painters, was ignored or ridiculed by the academic critics - one of his nudes was once compared to a 'mass of rotting flesh'. But gradually, a small and devoted band of enthusiasts developed.

One of them, Victor Chocquet, became a particular admirer and proceeded to form a considerable collection of Renoir's work. This gave the painter enormous confidence at a difficult time, but on its own it was not enough to support him. He was still dependent on portrait commissions gained via the Salon, until enlightened middle-class families like the Charpentiers and the Berards became his patrons, enabling him to continue with the more experimental Parisian scenes.

Through all these years Renoir had remained a bachelor. There had been romances, probably including one with Lise Trehot whom he painted so often in the 1860s, but Renoir seems always to have regarded the idea of marriage and children as a distraction from the focus of his life - painting.

But around the age of 40, he met Aline Charigot, a pretty girl some 20 years younger than himself, who had occasionally modeled for him. Their relationship developed during the summer of 1881, while he was working on the great masterpiece of his Impressionist period, The Luncheon of the Boating Party, for which she was one of the models. He taught her to swim, and they danced and went boating together. The gentle Aline had almond eyes and 'she walked on the grass without hurting it', but though they loved each other, their affair was not to be straightforward.

Renoir was at a crisis in his painting. Despite Aline's suggestion that they should go and stay in her small home village in Burgundy, he was reluctant to leave Paris and equally reluctant to have children. Aline called things off. Renoir started to travel intensively: first to Normandy, then Algeria, a country he associated with Delacroix, then to Spain and Italy to see the works of the Old Masters - Velazquez in Madrid, Titian in Venice, and Raphael in Rome - and the murals at Pompeii.

A wife and children

But Renoir did not forget Aline, and returned to Paris to be with her. It was to be a relationship of harmony and happiness. She brought him peace of mind as well as children to paint and, as he put it, 'Time to think. She kept an atmosphere of activity around me exactly suited to my needs and concerns.'

Back in his old Rue St Georges studio, Renoir absorbed the visual impressions of his travels into a new way of painting. The so-called 'harsh' style he developed first created further difficulties for his dealer, and it was only the huge enthusiasm of Americans for his work from 1885 that enabled Renoir to support Aline and their newly-born son in reasonable comfort. In 1890 the couple married. Though not yet rich, he was able to move with his family to a larger house in Montmartre and to take on help for Aline. Gabrielle Renard, a distant cousin of Aline's, arrived in 1894. Aged just 15, she had never before left the village of Essones in Burgundy where she and Aline were born. The rosy-skinned, dark-haired young girl soon became part of the family, helping to bring up the younger sons Jean and Claude, and frequently posed as a model.

Renoir enjoyed family life, working hard - and by now selling well - seeing friends every Saturday night, when Aline would hold 'open-house', and visiting his mother on Sundays. But disaster was soon to strike in the form of a serious illness. In 1897, he broke his arm falling off a bicycle, and this brought on the first attack of the muscular rheumatism that slowly started to cripple him and never left him free from pain for the rest of his life. By enormous force of will, aided by the devotions of Aline, Gabrielle and their friends, he somehow continued to paint.

To relieve the pain, Renoir spent increasingly long periods in the warmth of the South of France. In 1907, he built a beautiful house in Cagnes on the Riviera. With its many olive trees and orange blossom, and its views over the Mediterranean, 'Les Collettes' became his base for painting. The brilliant light and relaxed atmosphere helped ease his muscular pain and released a flood of creativity in a colorful, classical style.

However, the beauty of the place could not cure rheumatism. By 1908 Renoir could only walk with sticks. By 1912, his arms and legs were crippled and he was confined to a wheelchair. Nonetheless he continued to paint virtually non-stop, only halting briefly at Aline's death in 1915.

In his last years, Renoir took up sculpture - with two young sculptors acting as his hands, since his own were too crippled to use. The fact that these sculptures are unmistakably Renoir's bears witness to his exceptional ability to communicate.

Renoir painted to the end, working in a special glass studio in his garden. He was carried there daily in his sedan chair, always wearing his white out-of-doors hat, and placed in his wheelchair. Gabrielle would push the paintbrush between his twisted fingers. One day, after Renoir had painted some anemones a maid had brought him, he asked a friend to take his brush, saying T think I am beginning to understand something about it.' He died later that night, on 3 December 1919.

Painting for Pleasure

For Renoir, painting was a way of expressing his pleasure in life. He always enjoyed portraying his friends and lovers, and was never ashamed of making pretty pictures.

'Why shouldn't art be pretty?' Renoir asked once. 'There are enough unpleasant things in the world.' This simple statement sums up his attitude to both life and painting - he had a tremendous capacity for enjoyment, and his art was an expression of his pleasure in life. Renoir only worked when he felt happy, and he deliberately chose subjects that he considered attractive: lush landscapes, fruit and flowers, people enjoying themselves, children playing and, above all, beautiful women.

Nothing gave him greater pleasure than painting women, and although our idea of fashionable beauty may have changed considerably since Renoir's time, the young women we see in his paintings still evoke an era when living in Paris was fun. He was brought up the son of a tailor in the center of the city, and his models are invariably working girls - seamstresses, milliners, actresses -who, he once said, had the precious gift of living for the moment.

Natural as it seems now, Renoir's choice of subject matter was radical and daring when he decided at the age of 21 to enroll as an art student at the studio of Charles Gleyre. The Paris art world was still dominated by the official Salon, which preferred to exhibit works on historical and literary themes, painted in a realistic style. Only in the past few years had younger artists, notably Gustave Courbet, turned to everyday subjects which were more expressive of a fast-changing France. Renoir quickly found that he was more interested in life on the street corner than in the usual studio practice of copying plaster casts of antique sculpture. His teacher could not persuade him that the big toe of a Roman consul should be any more majestic than the toe of a local coal man. One day, exasperated with his pupil, Gleyre said, 'No doubt you took up painting just to amuse yourself. And Renoir replied, 'Certainly. If it didn't amuse me I wouldn't be doing it.'

The impressionist years

While studying at Gleyre's studio, Renoir became friendly with a group of fellow students, dominated by the dynamic personality of Claude Monet, who were later to become famous as the Impressionists. Together they went on painting trips to the Forest of Fontainebleau, 40 miles south of Paris, where they worked out in the open air. Renoir, very impressed by Courbet, used subdued browns and blacks in his work. But one day the artist Narcisse Diaz chanced upon him in the forest and, examining Renoir's canvas, asked 'Why the devil do you paint in such dark colors?'

This encouraged Renoir to use the lighter, rainbow colors he instinctively preferred and which he had learned to handle during his early years as a porcelain painter.

During the late 1860s, Monet and Renoir worked very closely together, for they were both attracted by sparkling river scenes and views of bustling Paris. Several of their pictures at this time are of almost identical scenes, but Renoir's style is softer and more delicate than Monet's. Working out of doors, where the light could not be controlled as in a studio, they had to paint quickly to capture the colors in nature before they changed - for example, when clouds covered the sun. So they made no attempt to blend their brushstrokes in the traditional way. Instead they placed different colors side by side, in the manner soon to be generally described as Impressionist.

Renoir enjoyed painting landscapes, but he was always more interested in people. Throughout his life he included his friends and lovers in his pictures - initially, as a penniless artist, they were the only models available to him. Some of their faces are distinctively 'Renoir, with almond-shaped eyes and luxuriant hair, but what he looked for especially in a model was 'an air of serenity and a good skin that 'took the light'. Some of Renoir's most successful early works are portraits, and his graceful, gentle style was particularly suited to painting children.

During his Impressionist years, Renoir developed a fascination with the effect of light passing through foliage to fall as dappled shadows on the ground, and on human forms. In his painting Le Moulin de la Galette, a large, complex composition, Renoir used the light passing through the trees to unite his figures with their surroundings. Although Renoir painted this work in his studio, he visited its location - a Montmartre dance-hall - every day, immersing himself in the life of the area and making sketches on the spot. Throughout the 1870s Renoir exhibited regularly with the Impressionists, but he also submitted paintings to the Salon. He was always more traditional than the other Impressionists and never for a moment considered himself a revolutionary. While his anarchist friend, the painter Camille Pissarro, wanted to burn down the Louvre, Renoir was a frequent visitor to the gallery.

A change of style

At first he saw no contradiction between his Impressionist insistence on painting directly from nature and his reverent study of Old Masters. But in 1883, following a trip to Italy, Renoir was no longer able to reconcile the two. He told a friend: T had traveled as far as Impressionism could take me and I realized that I could neither paint nor draw.' Subsequently, Renoir dramatically changed his style, and developed a 'harsh' technique, surrounding his figures with hard, sinuous outlines. In The Bathers (1884) he adopted the Old Masters' method of making detailed preparatory drawings. The resulting work is as flat and decorative as a mural at Pompeii.

By the 1890s, these harsh outlines had melted again as Renoir returned to a style more in harmony with his instincts. He began to use warmer colors, especially reds - possibly as a result of two earlier trips to Algeria where he had been most impressed by the hot, sultry light. He painted his children, their beautiful, robust nurse Gabrielle, and a variety of large, sensual nudes, all glowing with radiant color.

Renoir also did a number of flower paintings, in which he experimented with the same rosy flesh tints he used for his nudes. And at the end of his life, when his hands were increasingly crippled by rheumatism, Renoir began to execute small bronze sculptures with the help of studio assistants. These solid, rounded figures were yet another expression of his endless delight in the human form. T never think,' he said, 'that I have finished a nude, until I feel that I could pinch it.'

488 Renoir Paintings

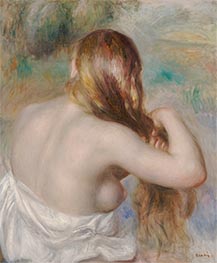

Blonde Braiding Her Hair 1886

Oil Painting

$822

$822

Canvas Print

$62.25

$62.25

SKU: RPA-18149

Pierre-Auguste Renoir

Original Size: 65.4 x 54.3 cm

Dallas Museum of Art, Texas, USA

Pierre-Auguste Renoir

Original Size: 65.4 x 54.3 cm

Dallas Museum of Art, Texas, USA

Modiste c.1875

Oil Painting

$824

$824

Canvas Print

$62.39

$62.39

SKU: RPA-18256

Pierre-Auguste Renoir

Original Size: 59 x 49 cm

Oskar Reinhart Museum, Winterthur, Switzerland

Pierre-Auguste Renoir

Original Size: 59 x 49 cm

Oskar Reinhart Museum, Winterthur, Switzerland

Vase with Lilacs and Roses c.1870

Oil Painting

$775

$775

Canvas Print

$63.08

$63.08

SKU: RPA-18522

Pierre-Auguste Renoir

Original Size: 65 x 54.5 cm

Private Collection

Pierre-Auguste Renoir

Original Size: 65 x 54.5 cm

Private Collection

Anemones in a Delft Vase 1910

Oil Painting

$662

$662

Canvas Print

$63.49

$63.49

SKU: RPA-18530

Pierre-Auguste Renoir

Original Size: 55.6 x 46.7 cm

Private Collection

Pierre-Auguste Renoir

Original Size: 55.6 x 46.7 cm

Private Collection

Vase with Anemones 1890

Oil Painting

$636

$636

Canvas Print

$49.98

$49.98

SKU: RPA-18531

Pierre-Auguste Renoir

Original Size: 42.2 x 33 cm

Private Collection

Pierre-Auguste Renoir

Original Size: 42.2 x 33 cm

Private Collection

Woman in a Garden (Woman with a Seagull Hat) 1868

Oil Painting

$898

$898

Canvas Print

$51.37

$51.37

SKU: RPA-19339

Pierre-Auguste Renoir

Original Size: 105.5 x 73.4 cm

Kunstmuseum, Basel, Switzerland

Pierre-Auguste Renoir

Original Size: 105.5 x 73.4 cm

Kunstmuseum, Basel, Switzerland

Landscape near Essoyes 1892

Oil Painting

$605

$605

Canvas Print

$64.41

$64.41

SKU: RPA-19340

Pierre-Auguste Renoir

Original Size: 46.6 x 55.2 cm

Kunstmuseum, Basel, Switzerland

Pierre-Auguste Renoir

Original Size: 46.6 x 55.2 cm

Kunstmuseum, Basel, Switzerland

The Boat c.1878

Oil Painting

$671

$671

Canvas Print

$62.94

$62.94

SKU: RPA-19754

Pierre-Auguste Renoir

Original Size: 54.5 x 65.5 cm

Museum Langmatt, Baden, Switzerland

Pierre-Auguste Renoir

Original Size: 54.5 x 65.5 cm

Museum Langmatt, Baden, Switzerland