Edgar Degas: The Enduring Legacy of an Impressionist Innovator

Edgar Degas, born in 1834, was not your typical Impressionist rebel. Sure, he walked alongside Monet and the gang, but he was never quite one of them. He preferred to lurk on the fringes, never fully buying into the Impressionist obsession with light and color. This year, we celebrate 190 years since the birth of this elusive genius, whose legacy remains both captivating and confounding. Degas was the quintessential outsider who simultaneously shaped the movement and distanced himself from it, leaving an indelible mark on art history, yet refusing to be pigeonholed.

Born Hilaire-Germain-Edgar de Gas into a wealthy Parisian family, Degas wasn’t the struggling artist stereotype. His father was a banker, his mother hailed from New Orleans, and young Edgar was afforded a privileged education. Initially destined for a legal career - imagine the tragedy! - Degas quickly veered off course and enrolled in the École des Beaux-Arts, following his passion for drawing and the Old Masters. He spent several formative years in Italy, sketching works by the likes of Michelangelo and Raphael, which rooted him in classical traditions even as his later work would challenge contemporary norms.

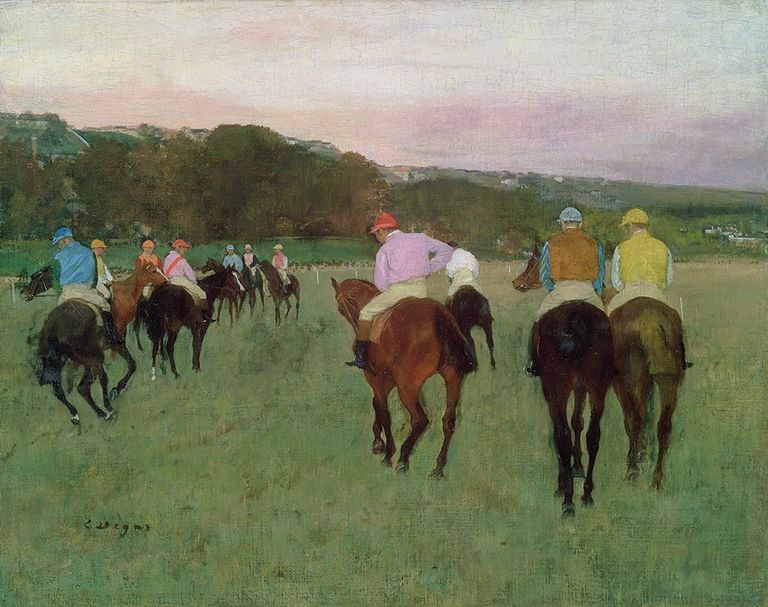

Degas’ early career was steeped in history painting - large, grandiose narratives straight out of academic tradition. But soon enough, the tides changed, and he found himself gravitating toward more intimate, everyday subjects. His fascination with modern life began to blossom, and he turned his gaze to the world of ballet dancers, café life, and behind-the-scenes moments in the theaters of Paris. But even here, his classical training remained apparent. Degas wasn’t interested in the fleeting light that so enraptured Monet, Renoir and his fellow Impressionists. No, Degas was all about the human figure, the structural integrity of the body, and the subtle, raw moments that conveyed the reality behind the performance.

He may have exhibited with the Impressionists, but Degas rejected the label, despised plein-air painting, and never truly embraced the movement's fascination with spontaneity. Instead, his compositions were meticulous, often sketched and revised endlessly in his studio before being painted. "The Bellelli Family," a massive canvas that took him years to complete, is a prime example of Degas’ painstaking approach. This haunting family portrait reveals his genius for capturing psychological depth - you can practically feel the tension among the figures, a stark contrast to the more harmonious scenes of family life often portrayed by his peers.

But let’s not forget Degas' famous ballerinas, the subjects of some of his most iconic works. Over half of his oeuvre is dedicated to these dancers, yet, contrary to popular belief, his portrayal of them was anything but glamorous. Pieces like "The Dance Class" and "Dancers in Blue" strip away the illusion of grace and poise, focusing instead on the grueling labor and the moments of exhaustion behind the art of ballet. He was fascinated by the human form in motion - not just its elegance but its awkwardness and imperfections. These dancers are real people, muscles straining, backs bent in concentration, not floating ideals of beauty. The backstage, sweaty, tired, and utterly human is where Degas’ art truly shines.

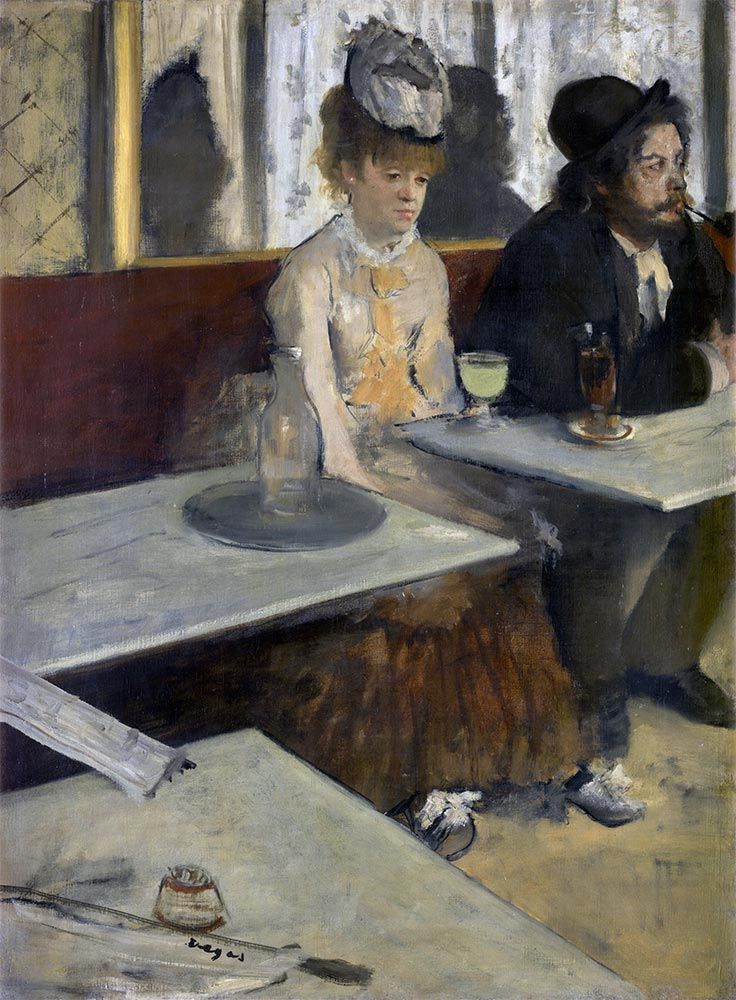

While ballet dominated much of his subject matter, Degas’ interest in the ordinary stretched beyond the dance studio. His "Absinthe Drinker," for instance, is a harrowing portrait of Parisian life - two lonely figures trapped in a state of ennui, staring into nothingness. No grand drama, no heroic moment - just a simple, bleak snapshot of modern urban existence. It’s the antithesis of the romantic Paris we often imagine. That’s Degas - cutting through the glamour and showing us what’s beneath the surface.

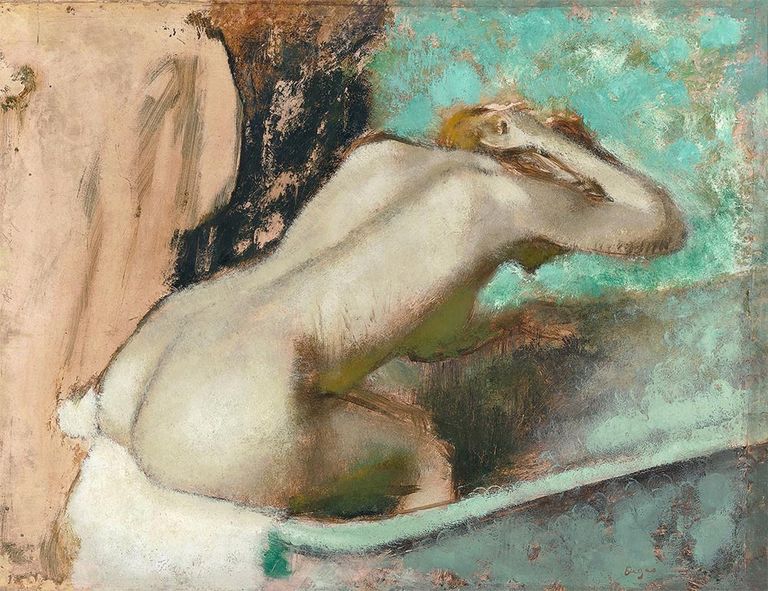

Degas was a man of many mediums - not content with just oil on canvas, he dabbled in pastels, sculpture, and even photography. His pastels are particularly noteworthy, especially as his eyesight began to fail later in life. His colors became more vivid, his forms less distinct, and his work took on an abstract quality as he delved into the world of pure expression. And let’s not forget "Little Dancer of Fourteen Years," a sculpture that scandalized the Parisian art world with its bold realism. Unlike the polished sculptures of classical antiquity, this little dancer was awkward, gawky, and very much a work in progress - a far cry from the smooth, idealized figures most critics expected.

Though he became increasingly reclusive and irritable as he aged - some say due to his deteriorating eyesight - Degas never stopped pushing the boundaries of his work. By the time he passed away in 1917, his influence had permeated the art world. His careful study of movement and his unflinching portrayal of life’s less glamorous moments paved the way for future generations of artists, especially those drawn to capturing the human condition in all its flawed beauty.

As we mark the 190th anniversary of his birth, it’s clear that Degas’ art remains as powerful and relevant as ever. His works continue to challenge, to provoke, and to reveal something raw and essential about human experience. And here’s the thing - those masterpieces? They’re not trapped behind glass in some sterile museum. They can live again, breathe again, as stunning oil painting reproductions at TOPofART or as exquisite giclée prints on canvas at TopArtPrint. Because art, much like Degas, shouldn’t just be observed. It should be experienced.

Comments